Joanne Merry, Technical Director at Carbon2018, discusses the importance of developing wellbeing strategies for new and existing healthcare buildings.

Florence Nightingale told hospitals that they needed more windows, better ventilation, improved drainage and more space. This was great advice in the early days of better, healthier buildings but today the challenges are far greater.

There are three main drivers of the healthy building movement. The first is a realisation that enabling healthy lifestyles can mean long-term savings in health treatment costs. The second is the clear evidence that the working environment impacts employee productivity, providing local authorities with a financial case for being concerned about workplace wellbeing. The third is that the next generation of employees, Generation Z, are not willing to compromise on health or happiness and demand nothing less than a work environment where wellbeing matters. For local authorities to attract, and keep, the best talent, a healthy building is a must.

It is likely to become common practice in the near future for local authorities to have a separate wellbeing policy for their buildings. Elements of wellbeing are already addressed in existing policies such as health and safety and sustainability, but these do not typically take a holistic view, nor do they go far enough. There are a number of voluntary wellbeing standards for buildings that are emerging, similar to those we have seen for energy and sustainability. These allow local authorities to go above and beyond the minimum requirements and demonstrate their commitment to the cause.

Local authorities should also consider that as smart building technology continues to evolve, they could find themselves being held to account by their buildings’ occupants. This is because, in the future, wearable technologies like smart watches may be able to tell us about environmental wellbeing factors such as air quality, lighting, humidity and noise levels.

Since we already have devices that track personal wellbeing parameters such as blood pressure, steps and sleep patterns, it seems natural that interest will soon turn to measuring the quality of our environment. When that happens, local authorities will need to make sure that their buildings conform to the wellbeing standards their occupants expect.

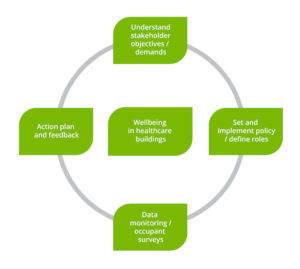

It is clear that having a wellbeing strategy in place is essential for successful healthcare estate management. The next question is how should local authorities approach developing one and what factors should they consider?

Understanding the building and its stakeholders

A wellbeing strategy will vary from building to building, taking account of its location, age and type, the systems it has installed, and the nature and purpose of its occupants. The first step towards developing a positive and proactive strategy will be to understand the demands and goals of the building and all those who have a stake in it.

Engaging with occupants to understand their motivations, rather than making assumptions about them, will go a long way towards achieving the very objectives a wellbeing strategy sets out to meet. At the same time, understanding the physical, technical, geographical and economical constraints of the building will dictate which wellbeing measures are possible and which are not. This includes engagement with all stakeholders such as health care staff, office staff, maintenance and facilities management, patients and visitors.

Defining wellbeing responsibilities

Once the constraints and objectives of the building and its stakeholders are understood, local authorities need to consider the different areas of responsibility that can be defined by a wellbeing policy. Who will be responsible for ensuring appropriate levels of thermal comfort, lighting and air quality?

A wellbeing policy will need to be concerned with the impact of individuals’ activities on occupant wellbeing. It is likely that we will see health and safety risk assessments evolve to look at softer wellbeing factors such as noise and smell. Then there are third parties to consider such as onsite maintenance teams and contractors and there is a need to understand how their activities impact wellbeing, and what practices they could adopt to feed into the building’s overall wellbeing policy.

Once roles and responsibilities are understood, targets and actions can be set for the different parties involved to support the policy objectives.

Gathering extra data and putting it to good use

Increased gathering and monitoring of data will be necessary to make sure the standards in a wellbeing policy are being met. Building management systems and energy meters already collect a wealth of data but it is likely that systems will be extended to cover wellbeing parameters such as air quality, CO2 and lighting levels.

But wellbeing is not only about numbers. Its very nature will require the collection of qualitative data on the feelings and perceptions of occupants as well. This qualitative data, which can be gathered via occupant satisfaction surveys, will need reviewing against the objectives and standards set out in the policy.

It is also important to remember that monitoring and maintaining performance against the policy standards is only half the battle. The other half is using the data to make adjustments to the policy itself. Wellbeing is not as black and white as health and safety and local authorities should be aware that objectives will evolve more quickly in the course of making buildings more comfortable places. Wellbeing policies should be fluid enough to allow for continual improvement.

New-builds versus existing buildings

A final consideration is that developing a wellbeing strategy for a new-build is typically very different to developing one for an existing building. With existing healthcare buildings, local authorities have to work within the confines of what is physically feasible and economically viable. With new-builds, wellbeing measures are increasingly considered and integrated at the design stage with a view to meeting future occupant needs. In many cases it will be easier to develop a wellbeing policy for a new-build because half the work is already done.