John Moss, head of social housing at EnviroVent, looks at how whole house ventilation can have a positive impact on health.

Since Victorian times, the relationship between poor housing and poor health has been clearly recognised. In the 19th and early 20th Century, diseases such as tuberculosis, cholera and typhus were directly linked to unsanitary, cold, damp and overcrowded conditions. This has been made even worse by the fact that England has one of the oldest housing stocks in the developed world.

It has been interesting to read the recent BRE ‘Full Cost of Poor Housing’ report, commissioned by the Government. In this, ‘poor housing’ is defined as that which fails to meet the current minimum standard of housing in England and has one or more of the Category 1 Health Housing Health and Safety Rating System (HHSRS) hazards.

There are many HHSRS hazards, including damp and mould growth, which is listed as Category 1 (high) risk. The report found that Category 1 hazards were responsible for 70% of the NHS costs associated with poor housing. The average cost of making Category 1 hazards acceptable was calculated to be £2,875 per property and the total cost of dealing with HHSRS Category 1 hazards in existing housing stocks would be nearly £10bn.

The report also revealed that the NHS could potentially save £600m pa if all the Category 1 repairs were carried out in housing. The report concludes that if vulnerable people continue to live in the poorest 15% of England’s housing this would cost the NHS around £1.4bn per year in first year treatment costs.

The report also revealed that the NHS could potentially save £600m pa if all the Category 1 repairs were carried out in housing. The report concludes that if vulnerable people continue to live in the poorest 15% of England’s housing this would cost the NHS around £1.4bn per year in first year treatment costs.

Damp and mould

The high visibility of damp and mould growth and the distress this can cause means it is one of the main causes of complaints for maintenance teams during the colder months. Social housing providers often address the problem of damp and mould growth by upgrading insulation, adding new heating systems, followed by re-plastering and re-decoration. All of these actions can help, but do not tackle the cause of the problem — a serious lack of ventilation. It is a common misconception that turning up the heating will prevent condensation — it does not and the only way of tackling condensation is by introducing adequate ventilation to a property.

In the past, the best way to tackle condensation and mould growth in one particular room was to fit extract fans in that room. This can certainly help and it is recommended to have fully operating extract ventilation in the kitchen and bathroom. However, many local authorities are taking a ‘whole house’ approach to improve ventilation throughout the property.

One such social housing provider in the North-east has invested in Positive Input Ventilation (PIV) from EnviroVent for 300 properties in the last 12 months, as a way of reducing mould and damp in its tenants’ homes. During the winter months, condensation and mould growth was becoming an issue for some tenants, which resulted in ongoing callouts and reactive maintenance by the housng provider’s repairs and maintenance team. This was costing them a significant amount every year in temporary treatments.

Cold bridging

One of the recent properties to be affected was typical of the problem. A two bedroom, two-storey house, it had black mould in one of the bedrooms. The housing provider’s maintenance team found that the main cause of the problem was a vaulted ceiling near the external walls of the property that had not been insulated, which was alongside a roof with 300mm of loft insulation fitted. This caused a major problem with cold bridging, which was made even worse by the bathroom extract fan not working in the property.

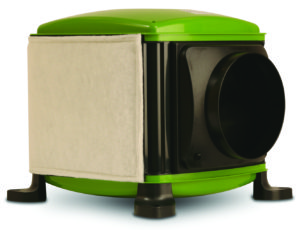

EnviroVent’s surveyor recommended a PIV system for the property and a number of others which were also experiencing issues. The whole house PIV and condensation control unit gently circulates air around the home from a central position on the landing in a house or the central hallway to transform a stagnant and stale atmosphere into a fresh, healthy and condensation-free environment.

The system provides a healthy living environment by supplying fresh, filtered air into a property at a continuous rate, which eliminates surface condensation, prevents mould growth and reduces house dust mite populations. The PIV systems are suitable for retrofitting and offer low energy consumption, so are very affordable to run. As a result, the company has received no further complaints of damp and mould from the properties where PIV systems were fitted over 12 months ago.

Humidity levels

Issues with damp and mould are worse in the winter months because relative humidity inside the home is higher. Everyday activities, such as bathing, washing clothes and people breathing generate moisture, whilst windows tend to be kept closed in the winter months trapping air inside. Without a continuous flow of fresh air into and out of a dwelling to control the relative humidity, the internal atmosphere may reach a high relative humidity of around 70-80%, which then leads to condensation. The water droplets that form on colder surfaces can result in mould growth and, in some cases, damage to the building fabric itself.

Many social housing providers are looking for permanent solutions to the issue of poor ventilation. Weary of mould treatments that do not work and with pressure from increasingly frustrated tenants, they are looking for longer term, effective solutions. Fit and forget systems like PIV are helping to improve the indoor air quality for tenants across the country, whilst reducing the risk of mould and damage to the fabric of a building.

The BRE report has highlighted how Category 1 hazards, such as mould growth, are costing the NHS dearly. Tenants are also becoming increasingly aware of the impact of damp and mould on their health, where it can exacerbate existing conditions such as asthma — and are therefore demanding permanent solutions. Social housing providers are increasingly taking a responsible approach by seeking long-term ventilation solutions that improve indoor air quality and have a positive impact both on the fabric of the property and the health of tenants.