When it comes to damp and mould: prevention is better — and often easier — than cure, says Wendy Thomas, Residential Product Manager at Nuaire.

Did you know that in England alone around 904,000 homes had damp problems in 2021(1)? Damp homes are unhealthy homes, affecting occupants’ physical and mental health, and prolonged dampness potentially damages the structure of the building.

Dampness in homes is most frequently the result of condensation caused by everyday activities, such as cooking and washing. When the humid air cools, or touches a cold surface, such as a window or wall, it condenses into liquid water droplets. It can also happen when the air becomes too humid, beyond its saturation point. A build-up of condensation is a common problem within homes of all types and sizes, especially in the winter months. If the humid air and the subsequent condensation are trapped within a property, it can lead to damp and mouldy conditions.

Our understanding of the dangers of living in damp and mouldy homes has been brought to the fore with the death of two-year-old Awaab Ishak in December 2020 from prolonged exposure to mould in his home in Rochdale. Subsequently, Awaab’s Law has been introduced as part of the Social Housing (Regulation) Act, which requires social housing landlords by law to fix damp and mould issues to strict deadlines (to be determined shortly), or rehouse tenants in safe accommodation. However, ‘fixing’ damp and mould has so often been approached from a ‘sticking plaster’ perspective.

Approaches to avoid

Approaches to avoid

By far the most common means of ‘dealing’ with damp and mould in homes is for landlords to treat the mould with chemicals. This will indeed remove the existing mould growth, but it won’t remove the mould spores from the air, which will continue to grow if the damp conditions remain. The spores will settle and in very little time the mould will regrow. Treating the mould is no doubt seen as a low cost, easy solution; a quick win. But is it, when you consider the repeat treatment costs, access issues, and the frustration of residents?

Dehumidifiers have risen in popularity over recent years, driven by greater public awareness of the potential home comfort and health benefits. But using dehumidifiers to tackle damp and mould is problematic on several fronts. They are designed purely to extract moisture from the air and will not generally remove indoor air pollutants, such as mould spores.

They tend to be switched on during the day only, but it’s the nighttime, when the heating is off, that the condensation starts to form. Compared to an extract fan, they are expensive to run and can be noisier. All in all, dehumidifiers are not a practical option, especially for social housing.

Practical solutions

The good news is there are practical, affordable solutions that all social housing providers can take to combat damp and mould. For existing properties, which form by far the bulk of social housing, Building Regulations compliant extract fans and Positive Input Ventilation (PIV) systems are an excellent option for both preventing damp and mould forming by extracting water vapour.

Mechanical Extract Ventilation fan

Everyone is familiar with extract fans, but there’s a good chance the ones you have in your properties will need upgrading as part of your planned maintenance schedules. The revised Building Regulations Part F (ventilation) was introduced in 2022, increasing minimum airflow rates in dwellings in recognition that previous ventilation levels were insufficient to reach all parts of a home, especially the bedrooms overnight if doors are kept shut. This will mean more powerful and efficient extract fans, such as Nuaire’s Cyfan fan, which is a powerful yet very quiet fan, or the new highly cost-effective Nuaire Faith-Plus Decentralised Mechanical Extract Ventilation (dMEV) fans.

Extract fans such as these that deliver the correct duty to meet Part F, prevent

condensation and mould from forming, but in properties that remain prone to damp,

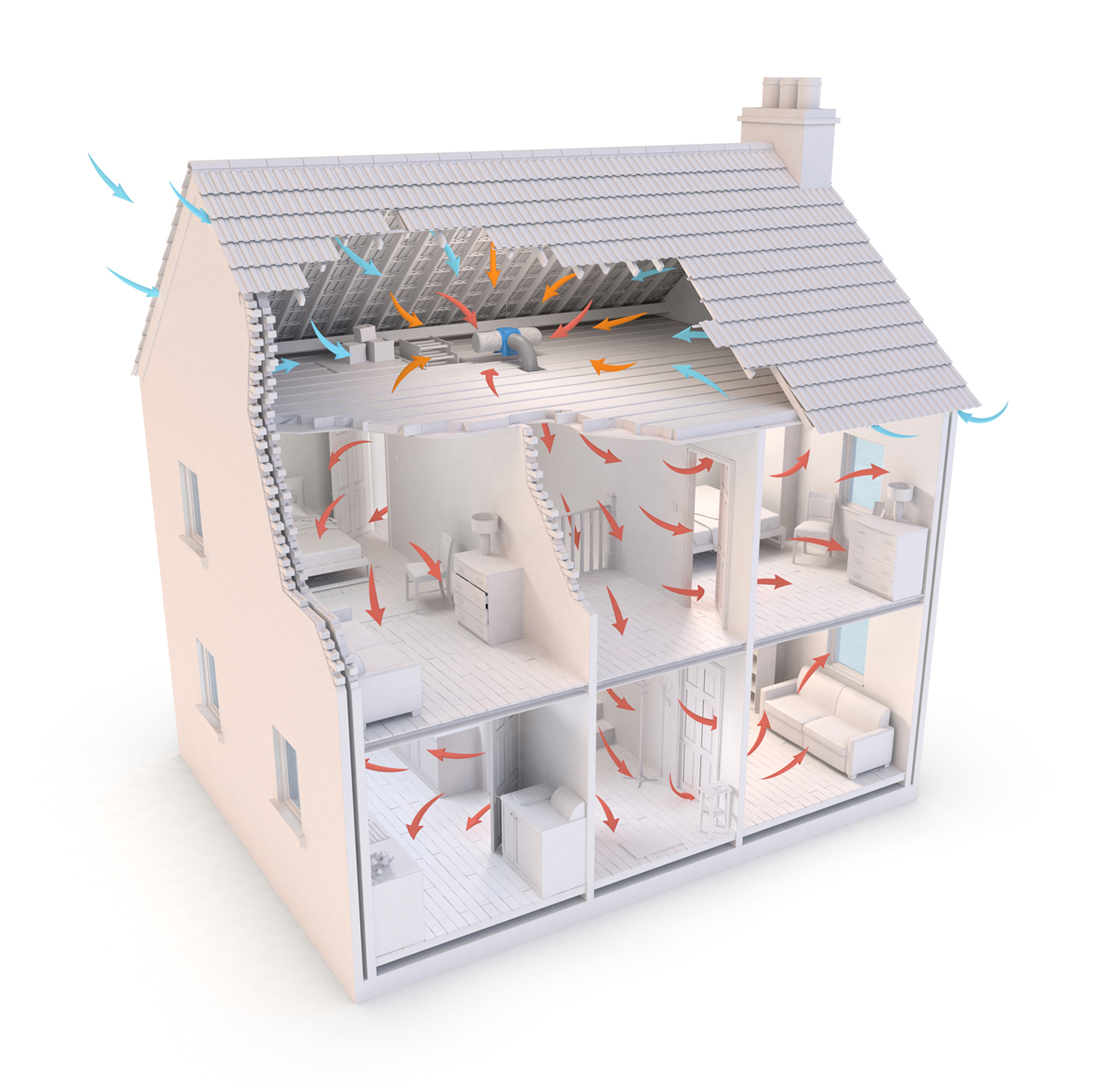

PIV systems, such as the Nuaire Drimaster-Eco, should be considered. They draw

fresh air into the loft space directly from outside which is then filtered before gently

dispersing into the home via a central diffuser at a continuous rate, encouraging

movement of air from inside to outside.

The great news is that they are inexpensive, quiet, reliable, and can be installed in less than an hour. Furthermore, some PIV system have the added benefit of filters, dramatically reducing harmful NOX and particulate matter levels within the home, which is ideal for properties in heavily polluted urban areas and for occupants with respiratory complaints.

dMEV continuous extract fans and PIV systems can also be used in new-build homes, but there is the further option of whole house mechanical ventilation here. Mechanical Extract Ventilation (MEV) systems actively extract air from ‘wet rooms’ via ducting to a central ventilation unit, which further ducts to an exhaust point.

Replacement fresh air is drawn into the property via background ventilators located in the habitable rooms and through air leakage. Mechanical Ventilation with Heat Recovery (MVHR), such as Nuaire’s MRXBOX, go one step further, combining supply and extract ventilation in one system, extracting and re-using waste heat from wet rooms. Clearly, these systems require extensive ducting, so are not practical for existing properties.

Managing the budget

Under Awaab’s Law, social housing providers are now legally bound to fix damp and mould issue in properties, with a focus firmly placed on identifying the causes, and introducing preventative measures. There’s no doubt this will place a financial burden on landlords big and small, but ventilation in the form of extract fans and PIV systems are not costly items, do not take long to install, and are long lasting.

[1] https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings published Feb 2023