The Grenfell Tower Inquiry’s recommendations will change how we build and maintain our buildings, says Nigel Sill, Chairman of Enfield Speciality Doors. But we don’t have to wait; we already know most of what we should be doing.

As designed and built the Grenfell Tower building had many good features: the concrete walls, ceilings and floors were non-combustible, the fire doors as originally fitted could contain a fire in a room for half an hour, which meant the fire brigade had a good chance of gaining access and extinguishing it. It would have been much better if there were two staircases to give residents evacuating the building enough room and time to get out safely and quickly, without impeding the fire brigade who were entering the building to fight the fire. A complete sprinkler system would also have been effective at reducing the spread of fire. Many new tall buildings have water tanks on the upper floors to support this.

On the 14th June 2017, at the time of the fire, it was particularly hot, and understandably many occupants had the windows open to help get a cooling airflow. It’s possible that many doors were also open, to improve the airflow and for convenience perhaps, so they would not have operated as intended in containing the fire. And although the advice was to stay in the flats on the assumption the fire could be contained in one room, long enough for the fire service to get there and deal with it before it spread, the fire spread so fast it rendered this guidance completely wrong.

It is now apparent the wrong cladding was put on the building for thermal and appearance improvements. It was also fitted incorrectly, which resulted in accelerating the fire.

Over time some doors had been replaced, and some of these were tested afterwards and failed after 15 minutes and not 30 minutes. However, if annual inspections had been carried out to check the integrity of the building, many non-conforming components could have been found and remedial action taken. For example, had any of the doors been changed? If so, was a fire certificate provided for both the flats and escape routes. Were both windows and doors suitable for a tall building? Was the cladding fireproof and did it have a zero spread of flame? Had any holes been made in floors, walls and ceilings for new services or repairs, e.g. broadband wiring, electrical wiring and plumbing and then had all these been fitted with appropriate fire-resistant filling?

The enquiry is still hearing evidence and no recommendations have been produced, but it would seem so long as the timber fire doors were properly fitted and kept closed, they work well and predictably.

It also transpired that it was not until many hours after the fire started, the main gas supply was turned off. As soon as this was done, the fire calmed down very quickly.

So, there are many lessons to be learnt and implemented, which must be done as soon as possible before another preventable tragedy occurs.

Sticking to the specifications

Good fire protection uses a mix of passive and active fire protection that work successfully together. Active fire protection systems such as sprinkler systems, fire extinguishers and smoke alarms operate in the event of fire to sound the alarm and put it out.

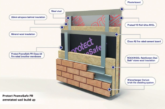

Passive fire protection uses systems such as fire-resistant walls, floors and doors that are built into the fabric of the building to slow or contain the spread of fire and smoke. Active measures such as sprinkler systems can be very expensive, and they may not always work properly. It’s not well understood or remembered that both active and passive measures need to be correctly specified, properly manufactured and installed, and need to be regularly maintained and monitored. If the building is maintained or modified then it needs to be restored to the specified fire protection. It’s very important that what is specified is what is installed and doesn’t get substituted for a lower spec, cheaper product.

As individuals and corporate entities, we’re used to the idea that we are legally obliged to keep our vehicles maintained and safe on the road. We’re used to the idea of regular check-ups and policing, the idea that we’re liable if we don’t. That idea, that people and companies are similarly responsible for the safety of their buildings, has not yet taken hold to the same degree.

Who knows about fire?

Recent research by Zeroignition among UK architects, commercial directors and specifiers as part of an international study, found that just over a third were unable to correctly define the concept of active fire protection and just over half were unable to do the same for passive fire protection. Almost three quarters were unable to define ‘fire resistance’.

Zeroignition Chief Operating Officer Ian King said none of the UK architects interviewed said they’d had comprehensive fire protection training. Most said they’d had some, but 8% had none. “There’s a lack of understanding as to the basics of fire protection which is worrying.” Jeremy Wiggins, Technical Director at Clerkenwell-based architecture and interior design practice gpad London, said it was easy for knowledge to become “half remembered” if it wasn’t used every day.

“We make it part of our design thinking from day one, involving end users and fire consultants as soon as practical,’ he said. ‘Beyond this we make sure each project has a named person for fire safety responsibility.”

We cannot eliminate the risk of fire but applying what we know can minimise the risk of damage to life and property. When the Grenfell Inquiry ends it is likely to recommend many things we already know we should be doing.

At every level, the industry needs to be better informed about fire. Specifiers need to be more knowledgeable, so fire safety is not compromised in the interests of energy saving or appearance. Changes to specifications should be challenged robustly to demonstrate equal or better fire resistance. Manufacturers should aim to pass fire tests by a comfortable safety margin and not aim to scrape through, because however careful people are you get variation in normal manufacturing and installation on site. Regardless of this variability, we need fire protection that provides building occupants and the fire service time to get in and out safely in the event of a fire. New buildings should be inspected and signed off as fire safe, and they should be inspected throughout their life to prove they remain safe and provide reassurance to building occupants and the fire service.

Value engineering versus ‘over-engineering’

Most importantly I believe we should rethink our attitudes to ideas like ‘value engineering’ and ‘over engineering’. In the perfect world when everything and everyone performs as we’d like them to, we can rely on 30 minutes to get in and out of a burning building safely. In an ideal world, products and systems can be value engineered to remove ‘excess’ value and cost, so they just scrape over the line. But in the real world that’s an unrealistic expectation.

In the real world, small product variations and the myriad of variations in how a building is built or maintained add up and eat into our safe time. In a fire that can result in loss of life and severe damage to property. The sum of small individual product and human variations can turn a safe outcome with a comfortable margin into a near-miss or catastrophe.

That’s why we deliberately ‘over engineer’ our Fire Doors so they have extra safety time built-in to every door, and why in recent tests sponsored by MHCLG, Enfield’s doors passed the tests with a reassuringly large margin: ‘opening in’ exceeded the time by 19% and ‘opening out’ by an exceptional 70% (51 minutes).

We need to know that the buildings we live in, visit and use every day – social housing, hospitals, schools, libraries, leisure centres and more – have a comfortable fire safety factor built in. The lessons learnt from Grenfell must be implemented quickly before another preventable tragedy occurs.

If it initiates a lasting change in our thinking as a nation, we’d all sleep a lot safer.